Article II 5/2024: SEABIRD-SAFE FISHING: GOOD FOR BIRDS AND GOOD FOR BUSINESS

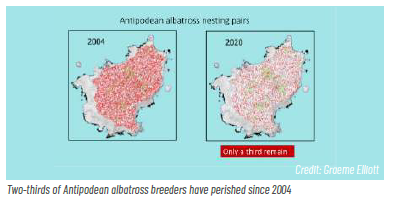

Blue 837 is a 37 year-old Antipodean albatross. Over the last 20 years twothirds of the breeding population has disappeared and the species could become extinct within our lifetime.1 To make matters worse, the female albatrosses are dying at a faster rate, and now, for every three males, only one female is alive.

Scientists Kath Walker and Graeme Elliott have spent the last thirty summers monitoring the population on the birds’ breeding island, an uninhabited rugged Sub-Antarctic island off the coast of New Zealand. “Every summer we return to the Antipodes Island and do a roll-call of birds in our study area. It is a heart-breaking job. Albatrosses normally live for 50 or 60 years, and mate for life. But with so few females left, widowed males like Blue 837 are a common sight”.

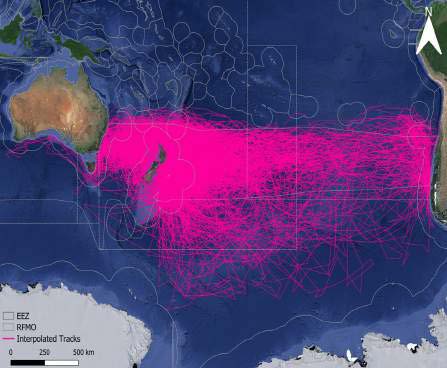

So, how and where are the birds dying, and why are the females so badly affected? The island itself is a safe haven, so Drs Walker and Elliott turned their attention to the albatrosses’ lives at sea.

The tracking program solved the mystery of the disappearing females. The study found males and females feed in different ocean areas, and unfortunately for the females, their range overlaps with an area of intense tuna longline fishing.3 Seven albatrosses carrying tracking devices have stopped transmitting near longline fishing boats, and in two instances the companies confirmed they had caught the bird.

Because there are so many fishing vessels, even if only a few albatrosses are caught by one vessel, it is a problem. For example, if a vessel hooks one Antipodean albatross every two months, and this is scaled up to the 400 vessels fishing in the same area as the birds, then 2 400 Antipodean would be hooked in a year. This would be enough to cause the population to collapse, which is in fact happening.

Unlike some albatross species, Antipodean albatrosses are not suffering from the many other threats that seabirds face such as plastic ingestion, rats eating chicks, nest disturbance and loss of habitat.4 Fishing is the main threat. In some ways this is good news, because compared to these other problems this one is solvable. But we don’t have much time, with the population continuing to decline. Efforts to recover Antipodean albatross will benefit a wide range of other threatened seabirds, so we will get a great return for our efforts.

Keeping baited hooks out of sight

3) Bose, S. and Debski, I. 2022, ibid

4) Walker, K. and Elliot, G. 2017, ibid

5) Melvin, E.F., Guy, T.J. and Read, L.B. 2014. Best practice seabird bycatch mitigation for pelagic longline fisheries targeting tuna and related species. Fisheries Research 149: 5-18 Robertson, G., Ashworth, P., Carlyle, I., Jiménez, S., Forselledo, R., Domingo, A. and Candy, S.G. 2018. Setting baited hooks by stealth (underwater) can prevent the incidental mortality of albatrosses and petrels in pelagic longline fisheries. Biological Conservation 225: 134-143 Sullivan, B.J., Kibel, B., Kibel, P., Yates, O., Potts, J.M., Ingham, B., Domingo, A., Gianuca D., Jiménez, S., Lepepe, B., Maree, B.A., Neves, T., Peppes, F., Rasehlomi, T., Silva-Costa, A., and Wanless, R.M. 2018. At-sea trialling of the Hookpod: a ‘one-stop’ mitigation solution for seabird bycatch in pelagic longline fisheries. Animal Conservation 21: 159-167.

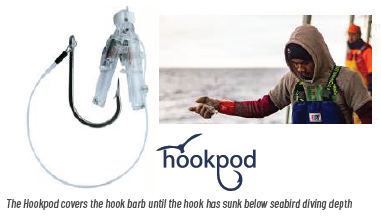

There are two more recent innovations, both proven to be highly effective. The Hookpod is a small device that a crew member closes over the barb of the hook during the line-setting operation.7 This means if a seabird attempts to take a bait it cannot be hooked. The Hookpod has a pressure sensor, and it opens up once it reaches a pre-set depth, usually 20 meters.

Albatrosses and other types of seabirds spend most of their lives on the high seas, beyond the jurisdictions of individual countries.9 And because the high seas are where most tuna longline fishing effort occurs globally, this is where we need to focus our efforts if we want to recover threatened seabirds like the Antipodean albatross, and shift tuna longline fishing onto a strong sustainable footing.

Complete web-based information toolkit

You might also find it helpful to assess how seabird-safe your current fishing is, and how to improve this. By selecting your fishing zone, and your current mitigation measures, you will be able to assess how well you are currently reducing seabird captures, and what additional measures will provide you with more protection. Information on the cost of the measures, where to source them, and how to use them safely and effectively, will be included.

And finally, you may be interested in communicating your efforts to reduce seabird captures to your important audiences, so you might find it helpful to learn how to verify the measures that are being used on your vessels. The toolkit will describe the ways this can be done; the most wellknown methods being dockside inspections, electronic monitoring or human observers. A South African company has developed a device that shows whether a bird-scaring line is in use, by measuring and recording tension.10 Also, Global Fishing Watch has developed an algorithm that uses a Vessel Monitoring System (VMS) and Automatic Identification System (AIS) to show whether a vessel is setting their lines at night.11

Each verification method has its strengths and weaknesses. Electronic monitoring, for instance, can detect whether a bird-scaring line is being used, and the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) has developed Artificial Intelligence (AI) that will make the footage review process faster and cheaper.12 But cameras cannot pick up some important design details about bird-scaring lines. This is where combining dockside inspections with electronic monitoring can provide greater assurance to stakeholders that the measures are well-designed and being used.

7) Sullivan et al 2018, ibid

8) Robertson et al 2018, ibid

9) Beal et al 2021. Global political responsibility for the conservation of albatrosses and large petrels.

10) ACAP Small Grant project “Development of a bird-scaring line compliance monitoring device” gets underway in South Africa. ACAP Latest News, 2020. Online: https://www.acap.aq/latest-news/acap-smallgrant- project-development-of-a-bird-scaring-line-compliance-monitoring-device-gets-underway-insouth- africa

11) Kroodsma, D., Turner, J., Luck, C., Hochberg, T., Miller, N., Augustyn, P., Prince, S. 2023. Global prevalence of setting longlines at dawn highlights bycatch risk for threatened albatross. Biological Conservation 283: 110026.

12) G Tuck, personal communication

Summary

We want both the tuna industry and seabirds to thrive – the health of each depends on the other. We encourage those of you who work in, and with, the industry to use your influence to encourage rapid uptake of seabirdsafe measures by tuna longline vessels. What is good for the birds is good for business.

Blue 837 still has a chance to find a new mate in his lifetime if we stem the losses of female Antipodean albatrosses and ensure young birds grow up to breeding age.

Note: The first iteration of the online Seabird-Safe Fishing Toolkit is available for testing and feedback at: (https://www.doc.govt.nz/seabirdsafe- fishing-toolkit). For further details, contact Janice Molloy (janice@ southernseabirds.org)

14) Marine Stewardship Council. 2024. Sustainable Tuna Yearbook 2024: Market data, innovations and insights from communities protecting our ocean. MSC. Online: https://www.msc.org/docs/default-source/defaultdocument- library/stakeholders/tuna-news/msc-sustainable-tuna-yearbook-2024.pdf?Status=Master&sfvr sn=99c3a154_14/MSC-Sustainable-Tuna-Yearbook-2024%20.pdf